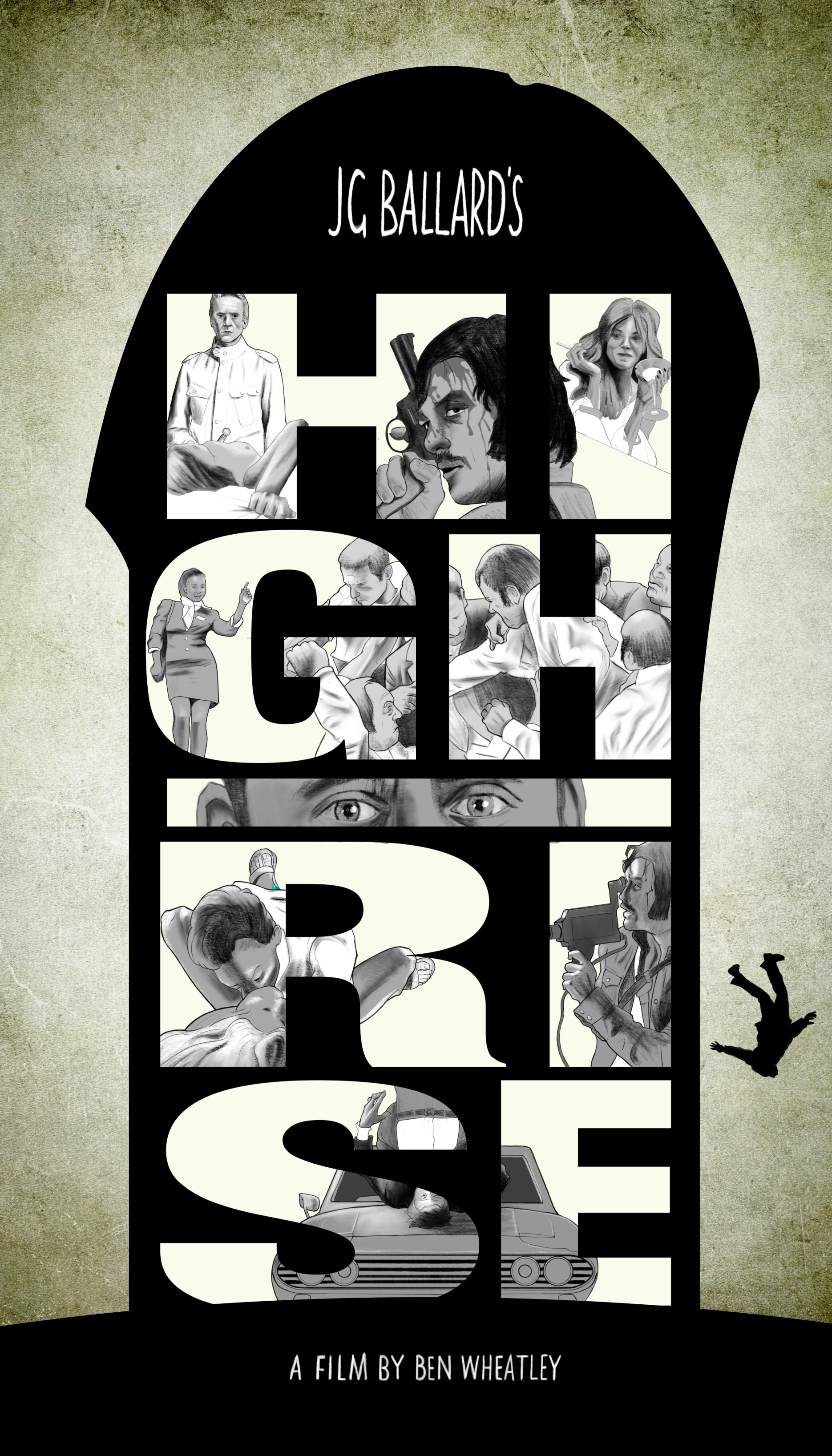

It looks like the unconscious diagram of some kind of psychic event.

—Robert Laing

Ben Wheatley’s ‘High Rise’ is a riot of a film. Visually and aurally it’s a stunner: ‘Apocalypse Now’ meets anything by Greenaway all wrapped up in Clint Mansell’s brilliant score. Despite its ‘surreality’ and attempt to ‘film the unfilmable’ it’s not difficult to follow. This is based on one of J.G. Ballard’s more coherent works.

Set in the eponymous High Rise we witness the descent into hell of its residents as they battle the building and each other with all the horror and dark humour the budget has available. We’re not quite sure why it happens except that maybe the building itself needs it, induces it, to feed off all the unfocused rage like some despotic machine.

Thatcherism, perhaps…

The building was designed for the individual not the group.

—J.G. Ballard, High Rise

Set in pre-Thatcher mid-70s Britain shortly before our former PM announced the end of society, this was a time of economic decline, unemployment, and power cuts. It also established the era of the concrete Tower Block which ripped long established communities from ground level and hung them from the clouds.

Social policies have consequences…

Although the film is shot around and held together by the character of Robert Laing, played with expert detachment by Tom Hiddleston, it’s the character of Richard Wilder who drives the plot. Played to the hilt by Luke Evans, like a version of Oliver Reed on bad drugs, Wilder is the human, all too human element who refuses to comply with the building. He’s a remnant of humanity trying to remember itself.

He touched himself like he was discovering his body for the first time.

—J.G Ballard, High Rise

Wilder is fighting back. At first with a movie camera and then with his fists. Not everyone approves, principally the building architect (Jeremy Irons) who wants Dr Laing to perform surgery, to which he replies: “I will not lobotomise Richard Wilder, he’s possibly the sanest man in the building.”

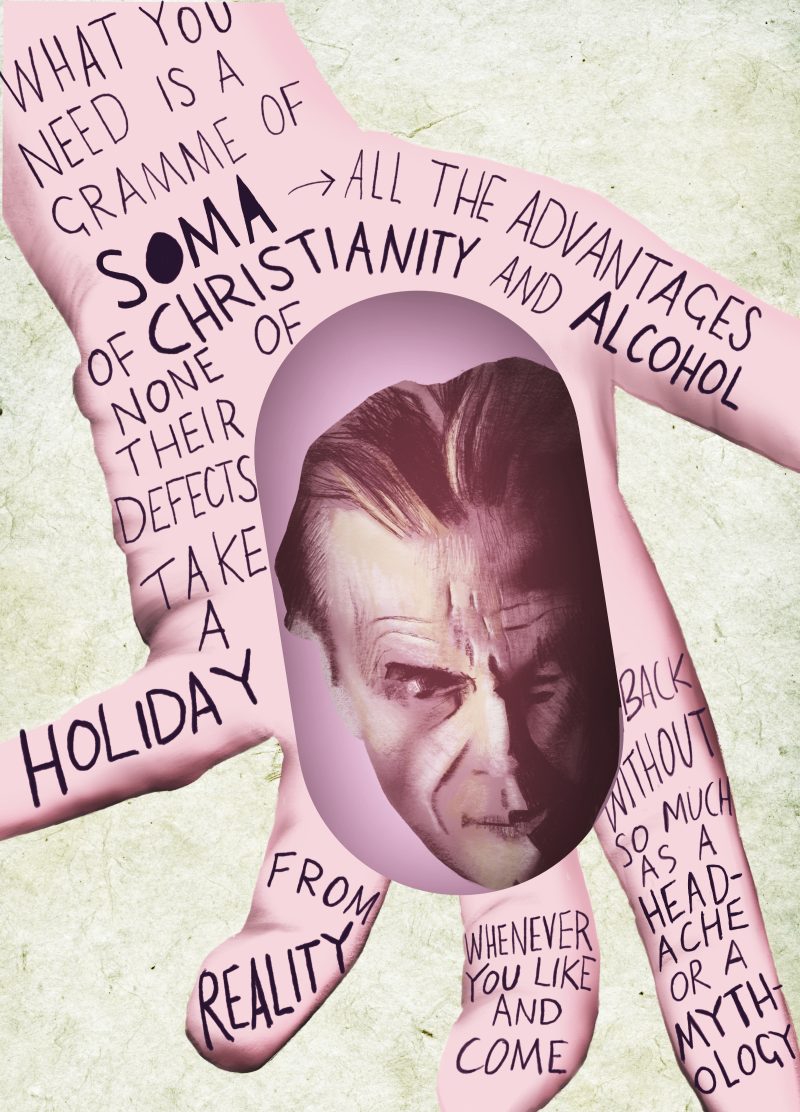

Although Wilder at times appears to be the working class rebel upstart, this is not the dystopia of Orwell’s 1984. It’s more in line with Aldous Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’. The book is clear that this is a luxury high rise (the higher you live the deeper your pockets) and the class divisions are middle versus upper middle, topped off by some super rich. The consumerist paradise has been bought and paid for, the only way is further up.

So are we watching political allegory or some other kind of cultural implosion..?

The film doesn’t seem quite sure but still manages to pull it off.

Closing to the strains of a Margaret Thatcher speech and The Fall’s ‘Industrial Estate’ the dark comedy puts a broad and satisfied smile on your face.

Well it did on mine anyhow…

So far so surreal. But is it Ballardian? And should we care?

I have deep love for a certain kind of surrealism. The kind that releases scatalogical odours with a degree of ‘pataphysical intent.

I see this in Ballard.

Reading him is like sitting in a room that is slowly losing its air supply… as normality ebbs away panic gives birth to hallucinogenic chaos.

Ballard’s surrealism creeps. It emerges from the carefully plotted uncanny then grabs you by the throat as soon as you’re not looking. The rapid acts of violence may feel sudden and unforeseen but actually they’re carefully calculated and have a perverse rationale rooted in logic.

In ‘High Rise’ the movie, however, the lunatics take over the asylum far too soon. Controlled chaos becomes the new normal before we’ve had a chance to adapt to ‘strange’, and we’re launched head-first into the carnivalesque to revel in the spectacle of each successive outrage.

It’s a tad gratuitous.

In contrast, Ballard’s ‘spectacular’ contains a reflexive depth.

He was adroit at documenting the ‘car crash’. Literally and metaphorically he described the most violent slamming together of disparate elements, but he did it in slow motion. His genius was not just to present the ‘the car crash as a religious sacrament’ but have you believe in it.

The belief makes no sense, but that’s the point. Does any belief hold up under scrutiny? Especially one that suggests we might actually understand who, what and where we are…?

Are we awake inside our experience of living or are we somehow distanced from ourselves, sleep walking the aisles of some hyperreal supermarket seeking procreation amongst the frozen meat and irradiated vegetables..?

Ballard could certainly be described as ‘post-modern’, whatever that hackneyed term means today, but his post-modernism came with a moral compass. His apparent nihilism wasn’t his point it was his cutting tool.

There’s a Nietzschean zeal in his stripping away of layers of morality, and that’s when the real disquiet emerges, when you’re forced to ask:

“Am I capable of this..?”

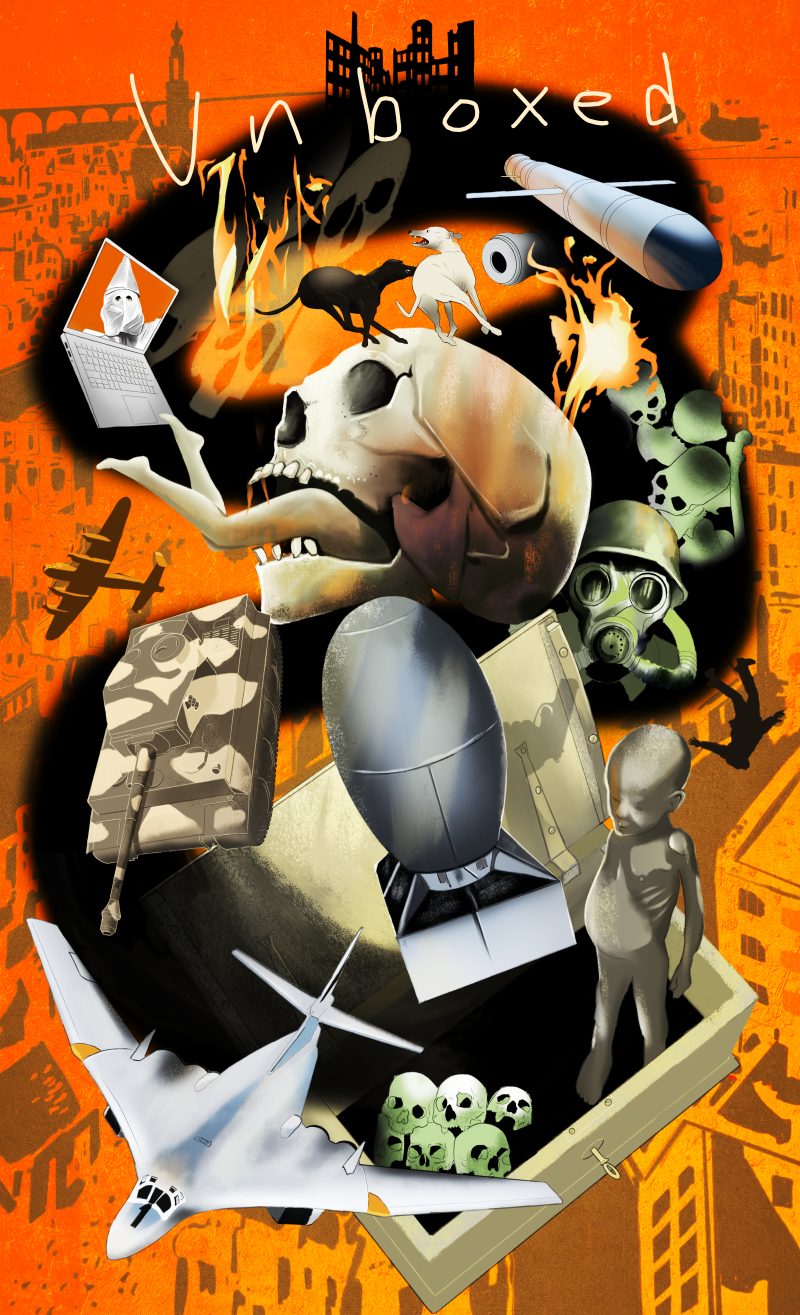

The spectacle of future past

Setting the film in the decade the book was written has generally been seen as a masterstroke. I disagree.

It certainly energises the surrealism but at the expense of the realism and in case you missed it Ballard, like the best surrealists, is rooted in reality.

The 70s were a decade apart in Britain. With lingering post-war deprivation sutured by brutalist architecture, social and economic decisions never hurt so much.

Viewed on the big screen, retrospectively, against a backdrop of failed housing projects we become voyeurs on the shortcomings of late modernism, presented as a ‘future past’ that never quite existed. Or did it..?

There’s moral ambiguity, a distance that lets us off the hook and allows us to be entertained. This doesn’t make it a bad film just a less Ballardian film.

Set in the present, in response to current national and cultural uncertainties, with a post-capitalist future beckoning, it could have been visionary, a truly Ballardian response to our crumbling (or evolving) sense of identity.

I await that screen Ballard.

In the meantime as dystopian visions go this one is messy but compelling. In Wheatley’s hands it might be a comment on the birth of Thatcherism and its maturation into modern neo-liberalism. Though I think that’s to lessen the movie experience.

If you haven’t already, go see. And if you haven’t already, read the book. They’re different things but like much in these collapsing times they sit together comfortably in the nebulous space of your mind’s eye to at some point copulate, and maybe create something entirely new.

It’s what happens in the mall.